I used Google Earth to visit Batam Island in Indonesia last week. The trip was certainly easier than the nearly 24 hours of flying and layovers required when I made the trip from Washington two decades ago, and the view from above was an exciting indication of changes on the island. But it was no substitute for being there in person.

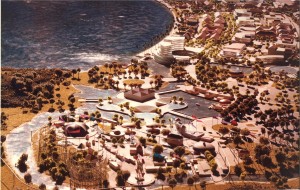

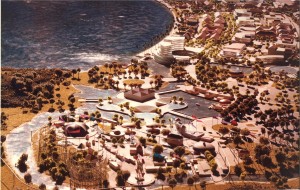

Google Earth view of Batam Centre, 2011

I spent Christmas of 1983 with a band of like-minded planners and architects on Batam Island. The rooms that we occupied were converted shipping containers, at one of the few hotels available. The power went out on Christmas Eve, an almost daily occurrence, as we gathered with flashlights and candles in one room to open a few gifts thoughtfully provided by our colleagues back home.  With the tropical rain pouring down, we turned in early to be ready for the big day to come.

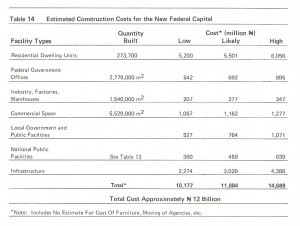

The story started a year earlier. Planning Research Corporation was engaged by the Batam Industrial Development Authority (BIDA), then part of Indonesia’s Ministry of Technology, to prepare a master plan for Batam Centre.  (British spelling seemed to be the norm for English usage in Indonesia.) We were teamed with an Indonesian firm, P. T. Atelier 6. Prof. Dr. Eng. B. J. Habibie, Minister of Technology and Chairman of BIDA, was determined that Batam should be a free-trade enclave and focus for economic development as part of the Straits of Malacca (Singapore Straits) region. (Habibie, who later became the president of Indonesia, continues to influence the island’s development.) The governments of Singapore and Indonesia had agreed to cooperate.

Batam's location, near Singapore

Batam is located about 20 km southeast of Singapore, a short hydrofoil ride from that high-tech island nation.. Batam Centre was to be the administrative and commercial core of the island, a thoroughly modern enclave that would be a comfortable entry for foreign investors and an attraction for vacationers seeking a taste of Indonesia’s rich and colorful culture. As project manager and team leader, I was determined that the plan should be a practical roadmap and model for improved living standards in a growing economy as well as a resource for marketing a nation.

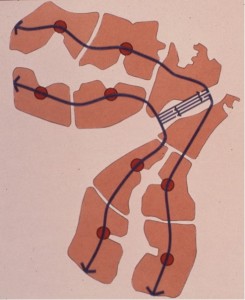

We conducted the usual economic analyses and demographic studies to project plausible population and income scenarios for the island and our emerging concepts of the new city’s role in the region. We extracted organizing principles from lessons learned about traditional villages and urban form, the social structure of Indonesia’s communities and neighborhoods, and the layers of government established to provide infrastructure and social services. We studied the topography, soils, hydrology, flora and fauna to understand the environmental opportunities and constraints that should shape development.Â

We thought about the educational and training requirements to produce a workforce to be employed by the businesses that might be attracted to Batam. We projected the demand for housing, schools and health care facilities, transportation, water, power, and waste management. We prepared tables of numbers, maps, sketches, and models. Batam Centre—an imagined place on the shores of Tering Bay, covered in mangrove and other tropical vegetation—began to assume for us all what I have come to call a “texture of credibility.â€

Batam Centre, planned on the shore of Tering Bay

"Dreaming in the daytime" on the waterfront in Batam Centre

We shipped our maps, drawings, models, and key members of our team to the island.  On Christmas Day we presented our 20-year plan to President Soeharto and his cabinet ministers. When one of the senior officials told me the plan seemed “very Indonesian,†I was pleased. Another told me we had helped them to “dream in the daytime.â€

Batam visitors' center, 1991

Scottish poet Robert Burns, wrote, “The best-laid schemes o’ mice an ‘men gang aft agley,†and so it was with our own scheme to continue working with BIDA to implement our Batam ideas. By May of 1984 our work was finished, left for others to consider. I was invited back in 1991 to review progress. Major roads were in place and our plan was displayed in the visitors’ center BIDA had constructed on the site we had proposed.Â

According to official statistics, Batam’s population today has grown about 50% from when we began our planning, to about 990,000. There are now 66 hotels and beach resorts on the island, with 5,600 rooms available. Foreign visitors to Batam average 100,000 monthly. BIDA is responsible for development in the BARELANG region, the three islands of Batam, Rempang, and Galang, now joined by new highway bridges, one of Indonesia’s designated “national development engines.â€Â

Perhaps it was chance, but I prefer to believe that the physical, social, and economic framework our team laid out 20 years ago has served its purpose as an infrastructure for Batam Centre’s development. If my satellite-enabled flyover is to be believed, the texture of credibility is becoming a reality.