Infrastructure provides an armature for urban development, and nowhere is this more apparent than in Abuja. Nigeria’s dynamic and restless capital city, now the home of some 800,000 people and maybe more than a million, sprang from the bush barely just over three decades ago. As the nation settled down from a civil war and ten years of military rule, the young constitutional government resolved to build a new city in the middle of the country. An international competition was held to select planners for the then-nameless capital. An American consortium won. In 1979, the master plan was published. (Disclosure: I was a member of the core group of International Planning Associates professionals and subsequently Chief Planner for PRC (Planning Research Corporation) Nigeria.)

The new city—the name Abuja, originating as a 19th-Century emirate, was transferred from a small city now called Suleja, just to the north—was to be centrally positioned and ethnically neutral in a nation of diverse tribal identities, a showcase for national unity and modern African

urban development. The underlying concepts were hardly revolutionary: Washington, DC, and many state capitals in the United States, for example, as well as Brasilia and St. Petersburg (Russia) had similar origins. In addition Lagos, the capital at the time, had grown beyond the capacity of its infrastructure; the city’s often chaotic services and gridlocked traffic threatened to choke the nation’s development.

The desire for Abuja to provide a strong image and sense of place, representing Nigeria’s position as the most populous nation in Africa and a rising democratic force in the continent were decisive in the mater plan’s development. As the capital, Abuja would have symbolic as well as political and economic importance. The siting of major government buildings and the layout of the transportation networks were intended to take advantage of dramatic topography and provide the matrix for a centralized urban form easily served by transit.

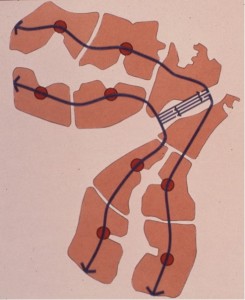

The plan’s curvilinear form was meant to serve the requirements for water supply and drainage by following the contour of the site in the shallow basin bounded by the Aso Rock and its surrounding hills. Parallel central transit spines and peripheral highways were planned to provide a framework for modular residential and commercial “mini-cities†that would be developed outward from the urban core as needed, each accommodating between 75,000 and 200,000 people and a full range of schools, healthcare, recreation, and other community services. The program for residential land and housing sought to balance the government’s desire for high living standards for its citizens and the planners’ projections of incomes and affordability within an advancing but still relatively

less-developed economy.  With a government-set target population of 1.6 million by the year 2000 and 3 million ultimately, Abuja was planned be the largest free-standing new city ever built. The federal government was to move from Lagos to Abuja by 1986.

It has been written that Daniel Burnham said, “Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably will not themselves be realized.â€Â Certainly Abuja’s master plan qualified as a grand scheme able to generate a certain excitement. While government functions would be the principal foundation for the city’s economy, the plan represented substantial private-sector investment opportunity and, to use developers’ vernacular, the numbers worked. However, speaking at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Houston in 1978, I noted it would not be easy. Threats to success could be foreseen in potential shortages of construction materials and labor, congestion of the poorly developed transportation network in Nigeria’s Middle Belt region, management challenges associated with such a large-scale undertaking, and the need for steadfast government support of the enterprise.

As it turned out, in the early stages of development some large buildings were constructed in advance of supporting infrastructure, so that government ministry workers in the early years labored under much-less-than-ideal conditions. The official shift of the capital to Abuja did

not occur until 1991. The Nigerian press reports that electricity, sewer, and telecommunications systems continue to be problematic. Housing and land use have remained sources of continuous conflict over the years, with the master plan cited variously as a myth used to justify forcible evictions of lawful residents and a neglected guide for balanced growth. (See, for example, a 2008 report from the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions.)

Scottish poet Robert Burns wrote, “The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men, Gang aft agley….†(To a Mouse, 1785) The thought is a suitable caution to Burnham’s successors.